By Aditi Venkatesh, Cognitive Science ‘21

Author’s Note: I wrote this piece for a UWP 104E assignment to explain the psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. I chose to focus on mental health because it holds personal value to me and addresses an often overlooked aspect of this pandemic. I support the creation of more accessible mental health services and hope to encourage people to reflect on their own mental well-being during these unprecedented times.

Recall your life just a few months ago. Hanging out with friends at a restaurant. Working in an office and chatting with coworkers. Sitting in a classroom with hundreds of classmates. Visiting family members. Buying groceries without worrying about wiping everything down. Going for a walk with neighbors.

Now, life looks a lot different. Zoom meetings all the time. FaceTime calls just to talk to friends and family. Paranoia about whether masks and gloves are covering your face and hands properly. Constantly checking social media for news. Using laptops every hour to communicate with classmates, coworkers, teachers, and pretty much anyone. The same routine repeated over and over again.

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a much different world. The consequences of this pandemic are primarily examined from a medical and economic perspective, but more attention needs to be brought to the psychological impacts of this pandemic. Mental health disorders have become increasingly prevalent in society; data from Active Minds, a mental health awareness organization, states that 50% of the United States population will experience a mental health condition at some point during their lifetime [1]. These statistics become even more concerning for young adults, with 75% of all cases of mental health issues beginning by the age of 24 [1]. With new layers of stress, anxiety, and isolation stemming from the pandemic, mental health issues are more widespread than before. Through the remainder of this piece, I will articulate outcomes of COVID-19 including the general effect of a pandemic on mental health, specifically focusing on younger populations at risk for anxiety and depression. I discuss alternative positive outcomes in people who normally thrive in times of limited social interaction and contrast this with the harmful impact of drastic isolation. I examine the benefits and consequences of increased technology use during COVID-19. Lastly, I have provided a few helpful mental health resources for students, and I urge everyone to assess their own mental health during these difficult times and advocate for better mental health services.

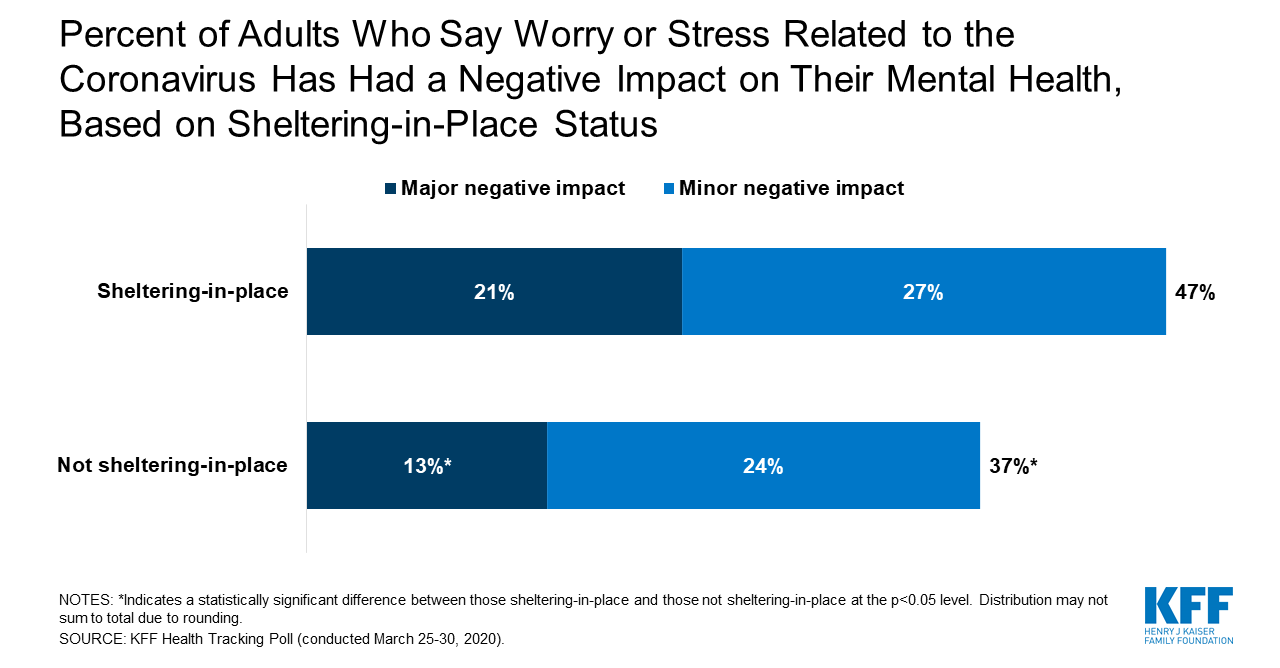

The coronavirus pandemic has created a mental health crisis across the world. Quarantining and shelter-in-place guidelines have isolated most people from family and friends, reduced social interactions drastically, and disrupted normal interpersonal interaction as shown in Figure 1 below, with data collected by the Kaiser Family Foundation towards the end of March 2020 [2]. People were already experiencing negative impacts on their mental health at the onset of the pandemic in early March, so undoubtedly, the duration of quarantine has exacerbated prior conditions. Individuals who are practicing shelter-in-place were more likely to report feeling mild or severe negative impacts on mental health than those who are not sheltering-in-place. Negative impacts include stress, anxiety, and general disruptions to life such as job loss, isolation, and income insecurity. These effects are particularly noticeable in individuals that were already at a higher risk for depression prior to the pandemic: younger adolescents, frontline healthcare workers, and individuals with chronic illnesses.

Figure 1:

Considering the isolation that comes with quarantining, we must recognize that levels of interpersonal dependence produce key vulnerabilities to depression and other comorbid mental health disorders. How much we depend on other relationships has strong implications on support systems, coping mechanisms to mental health issues, and willingness to seek treatment [3]. Prior research on psychosocial risk factors has shown that sociotropy and autonomy are two personality traits that predict depression. Sociotropy is the reliance on interpersonal relationships, while autonomy is related to independence and seeking self-control. A 2018 study conducted by Otani, et al. at the Yamagata School of Medicine in Japan found that sociotropy was associated with negative beliefs about oneself, but autonomy was associated with negative beliefs about others and short-lived positive beliefs about oneself [4]. These results highlight that dependence on others and an imbalance of self-esteem can be linked to depression. Since quarantining creates isolation, this isolation leads to an increased tendency to contemplate and overthink negative core beliefs about oneself, resulting in lower levels of confidence and self-esteem. We should be aware that certain personality traits are more vulnerable to depression during this pandemic and mental health needs to be prioritized more than ever before. However, one might wonder if autonomous individuals are thriving during this pandemic, since there is undoubtedly less social interaction than normal. For example, imagine a student that has mild social anxiety and does not enjoy their large classes in school. They might be relieved because they don’t have to have lengthy conversations with classmates and can independently complete their work. This very well may be the case for certain individuals. Previous studies have shown that autonomy can cultivate creativity, and introversion has been closely linked with autonomous tendencies [5]. Individuals that typically thrive in solitude and focus on hobbies, jobs, and other passions may find comfort in having more time to themselves due to COVID-19. Alternatively, extremely high levels of autonomy, such as complete disconnection from family and friends can be a factor that contributes to depression. This stresses the fact that a majority of individuals need some level of healthy social interaction to have a balanced life.

Despite the finding of a correlation between isolation and depression, since the onset of the pandemic, people are finding creative ways to socially interact and combat the loneliness COVID-19 has created. Many folks schedule weekly or monthly calls with family and friends to catch up. Organizations are holding virtual discussions about mental health and ways to practice self-care. Students across the world are creating online board games and holding virtual game nights.

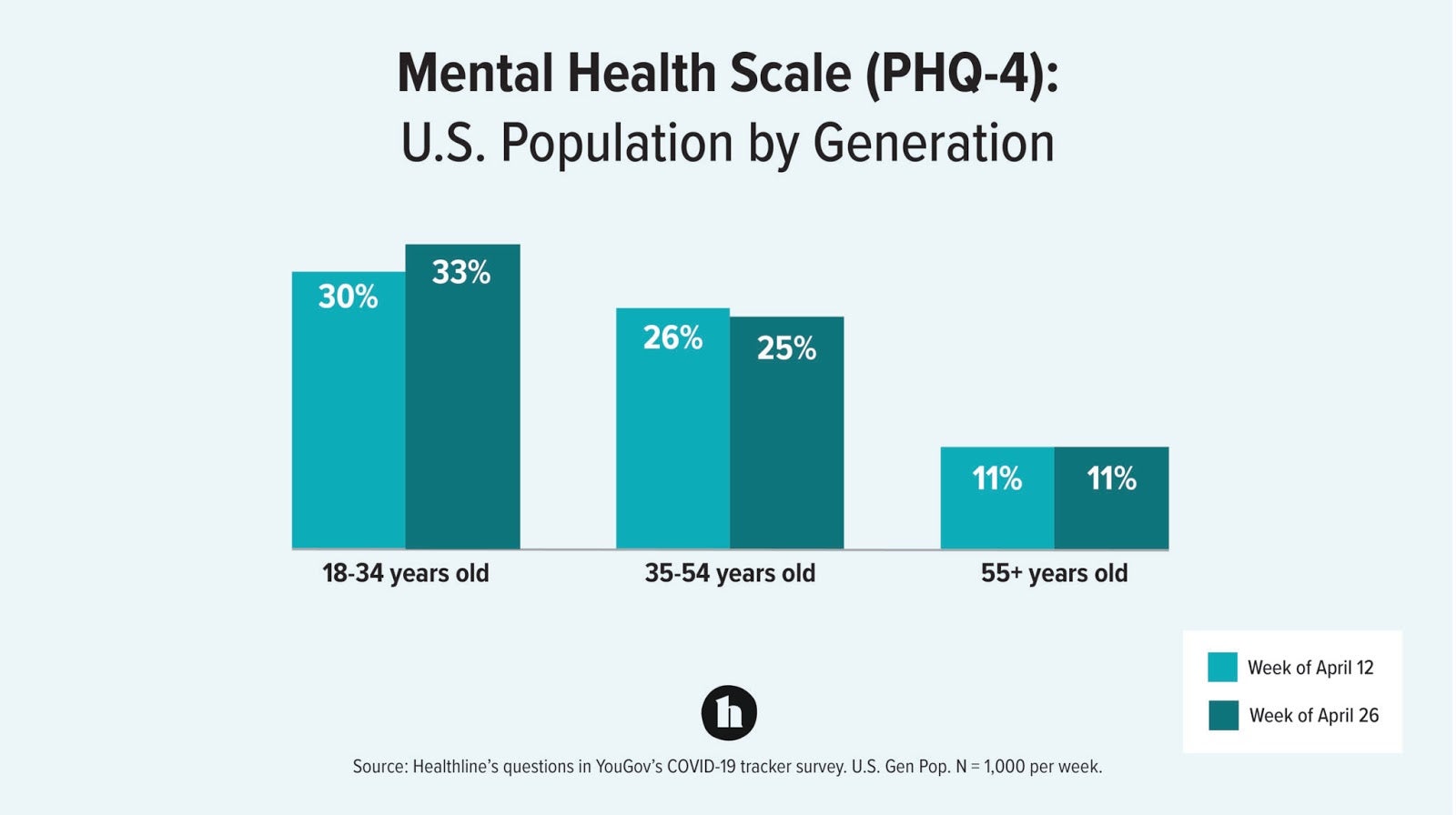

However even with these alleviating factors, the magnitude and ongoing duration of the pandemic’s restrictions continue to foster unusually high levels of loneliness. Students who may have participated in many extracurricular activities (which are now canceled), can’t talk to their friends as much, feel out of the loop in their lives, and struggle to find ways to spend their free time. Loneliness is one feeling that can contribute to depression and anxiety. In Figure 2, among data collected by Healthline through a YouGov COVID-19 Tracker during April 2020, the age group most affected by depression and anxiety (33%) was adults younger than 35 years old [6]. Additionally, this younger population showed an increase of anxiety and depression over a two-week span from April 12th to April 26th. Lastly, 45% of the U.S. population tested showed anxiety and depression PHQ-4 values out of the normal range [6]. However, older populations reported a plateau or slight reduction, which may be due to less dramatic lifestyle changes or less technology use compared to younger generations. This is significant because it illustrates that younger adults, which includes most students, disproportionately face worsened mental health.

Figure 2:

At the same time in China, researchers found similar patterns of anxiety and depression and chose to analyze why this exacerbation was present in younger individuals. Many research studies in China, where the peak of COVID-19 has passed, are examining the psychological repercussions of the pandemic, with a focus on depression and anxiety. In a published study from April 2020, researchers in Wuhan, China measured that the prevalence of depression and anxiety in the general population was 35.1% and 20.1%, respectively [7]. Further analysis of the self-report questionnaire confirmed that individuals younger than 35 years old reported more severe symptoms of depression and anxiety. In fact, among the younger population, those that spent more than 3 hours per day thinking about the pandemic faced more severe anxiety than those that spent 0-2 hours. This result highlights that in addition to actual lifestyle changes, thoughts about COVID-19 induces anxiety in young populations. This begs the question, why are younger people thinking about COVID-19 more than older people?

The answer is technology. Even though everyone uses technology, younger ages rely on technology more, especially for school and interacting with friends. Of course, technology is not all bad. In fact, society is most likely only able to function during this pandemic due to advancements like video conferencing, telemedicine, and online social groups. However, another study conducted in Wuhan, China explored the use of social media during the recovery interventions placed after the peak of COVID-19 [8]. Researchers found that social media support groups slightly reduced depression. But more significantly, adults that spent more than 2 hours on COVID-19 news on social media had increased anxiety and depression. Another study in Chicago in May 2020 explored the role of mainstream media in coronavirus news and depression. Researchers found that greater exposure to COVID-19 news, through cable news channels like CNN, local news channels, and the New York Times, led to higher perceived vulnerability to COVID-19, and this was strongly correlated with depressive symptoms [9]. Social media and mainstream media sources can both produce an undue burden on individuals through a barrage of stressful information about COVID-19 and lead to greater anxiety and depression.

Another form of technology, while useful for work and school, has unintended negative consequences: video conferencing. People have started to refer to these downsides as “Zoom fatigue” [10]. Zoom fatigue is the phenomenon where people are more tired and stressed with online meetings compared to in-person ones. I am sure many readers have experienced the similar stresses of looking presentable, awkward silences when nobody is speaking, and simply, less fun meetings. During Zoom meetings, it is difficult to discern normal social cues, such as body language and eye contact, over a video. This nonverbal communication is crucial to making conversations run smoothly. Removal of many social cues makes video calls feel impersonal. It can make even a catch-up video call to your best friend seem stressful. Additionally, previous research has shown that when responding online, even delays of up to 1.2 seconds can make a person seem unfocused and unfriendly [10]. These slight technological delays can dramatically contribute to greater stress and anxiety. Zoom fatigue can be especially taxing on younger populations that are still in school and are constantly in and out of Zoom meetings for courses.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, society finds itself at crossroads. How do we balance the positive and negative impacts of the technology use? Obviously, we cannot simply get rid of Zoom meetings and online classes; however, this pandemic gives us a crucial opportunity to expand online mental health services. Past research on mental health effects during the 2003 SARS epidemic in China showed similar prevalence of worsened mental health, with 48% of the participants reporting deteriorated mental health because of the SARS epidemic through anxiety and depression; this is very similar to the 47% found in the 2020 KFF study [11, 2]. If mental health issues are just as exacerbated in our pandemic 15 years later even with greater technological advancements, it accentuates the disparities in accessible online mental health care. Increasing virtual therapy appointments, online support groups, and videos for stress-relieving techniques like meditation, breathing exercises, and self-reflection are some starting points.

A CDC study conducted in June 2020, several months following the onset of the pandemic, found that people aged 18-24 years still face the highest prevalence of mental health conditions [12]. However, 30.9% of all participants showed anxiety and depression symptoms above normal PHQ-4 measurements; this illustrates a reduction compared to the finding of 45% measured in the April 2020 Healthline survey [12, 6]. Most importantly, I hope this shows that things are getting better. I especially encourage all readers to reflect on how to better take care of their own mental health. It is so important to practice self-care, which can be different for everyone! This can be exercising, seeing a therapist, hanging out with friends, getting more sleep, or setting boundaries for your own capabilities. It’s okay to prioritize your mental health when things get overwhelming. Therapy can be helpful for some folks, so here are some resources to be aware of. Student Health and Counseling Services offers on-campus counseling appointments for students (call (530) 732-0871 or visit hem.ucdavis.edu to schedule). Free tele-mental health and online counseling appointments are offered through Therapy Assistance Online (visit taoconnect.org and sign up with your UC Davis email). Text RELATE to 741741 to chat live with a crisis counselor, available 24/7 through the Crisis Text Line. Lean on your support systems and know that you are not alone! Mental health is just as important as your physical health. I hope we can take this time to acknowledge the mental health crisis this pandemic has created by improving available mental health services and making mental healthcare more accessible for at-risk populations.

References

- Statistics. (2020, June 24). Retrieved August 07, 2020, from https://www.activeminds.org/about-mental-health/statistics/

- Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Orgera, K., Cox, C. F., Garfield, R., Hamel, L., Muñana, C., & Chidambaram, P. (2020, April 21). The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

- Meissner, B. L., & Bantjes, J. (2017). Disconnection, reconnection and autonomy: four young South African men’s experience of attempting suicide. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(7), 781–797. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2016.1273512

- Otani, K., Suzuki, A., Matsumoto, Y., & Shirata, T. (2018). Marked differences in core beliefs about self and others, between sociotropy and autonomy: Personality vulnerabilities in the cognitive model of depression. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 863–866. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s161541

- Runco, M. A., & Pritzker, S. R. (1999). Encyclopedia of creativity. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Healthline Mental Health Index: Week of April 26 – U.S. Population. (2020, May 14). Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/press/healthline-mental-health-index-week-of-april-26-u-s-population

- Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group? Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1-12. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438

- Ni, M. Y., Yang, L., Leung, C., Li, N., Yao, X. I., Wang, Y., Leung, G. M., Cowling, B. J., & Liao, Q. (2020). Mental Health, Risk Factors, and Social Media Use During the COVID-19 Epidemic and Cordon Sanitaire Among the Community and Health Professionals in Wuhan, China: Cross-Sectional Survey. JMIR Mental Health, 7(5). doi: 10.2196/19009

- Olagoke, A. A., Olagoke, O. O., & Hughes, A. M. (2020). Exposure to coronavirus news on mainstream media: The role of risk perceptions and depression. British Journal of Health Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12427

- Sander, L., & Bauman, O. (2020, May 22). Zoom fatigue is real – here’s why video calls are so draining. Retrieved from https://ideas.ted.com/zoom-fatigue-is-real-heres-why-video-calls-are-so-draining/

- Lau, J. T., Yang, X., Pang, E., Tsui, H. Y., Wong, E., & Wing, Y. K. (2005). SARS-related perceptions in Hong Kong. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 11(3), 417–424. doi: 0.3201/eid1103.040675

- Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M.W. (2020, August 13). Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24-30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2020, 69, 1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1