By Vishwanath Prathikanti, Anthropology ‘23

Author’s note: I, like many around the world, was alarmed when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its sixth assessment report in August 2021 and delivered news of rapid and intensifying climate change. As an undergraduate with a research focus on science education, I was almost equally alarmed to find that the National Center for Science Education reported that 40% of middle and high school teachers teach climate change inaccurately. Furthermore, climate change isn’t required to be taught, or addressed in any capacity, in any state. In an era where climate change is becoming an existential threat to humanity, I wish to highlight the faults in climate change education and explain how it must improve.

In schools across the United States, teachers are teaching subjects such as arithmetics, the Revolutionary War, Shakespeare’s plays, and, more recently, climate change. However, not all teachers teach climate change, and the ones who do may be teaching it wrong.

Before we discuss climate change education, it is important to understand exactly what has caused the degree of climate change in the past few decades. All credible scientists agree that climate change is happening, and it’s human activities that are responsible for causing it. Our atmosphere is designed to keep heat from the sun inside; it’s why we don’t completely freeze at night when the sun isn’t directly on us. Greenhouse gasses, such as CO2 and methane, help our atmosphere keep this heat in. Since the mid-twentieth century, humans have been significantly increasing the amount of greenhouse gasses in our atmosphere, either by driving cars that produce carbon dioxide, raising livestock, which produce methane, or cultivating soil, which produces nitrous oxide [1]. This results in more heat being trapped in the atmosphere, causing increased floods and droughts, the destruction of coral reefs, and the displacement of animal populations.

Considering the fact that the United States had the second greatest carbon footprint in 2021, it is imperative that the next generation understands the reality of climate change [2]. If nothing is done to address climate change, irreversible damage will be dealt to the Earth, such as animal and plant populations going extinct and even human settlements being destroyed or simply deemed uninhabitable due to worsening weather conditions. People must be educated on the severity of climate change so that they may mitigate or prevent such catastrophic events.

What does climate change education look like now?

Despite climate change being an existential threat to humanity, climate change education isn’t actually required to be taught in schools. Topics discussed in school are left for states to decide, and in many states, including California, teaching climate change is not mandated, despite it aligning with state science education standards [3, 4]. This leads to varying levels of quantity and quality regarding climate change education, as it often falls into the hands of individual schools or teachers themselves to determine how much time they spend and the level of depth when discussing climate change.

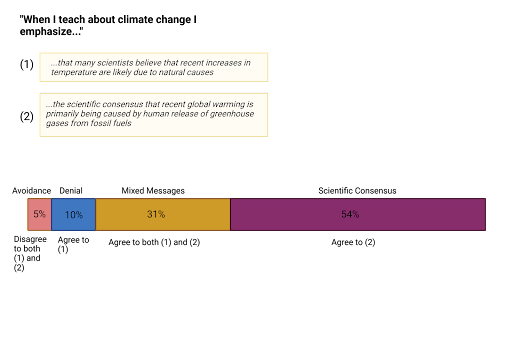

A study done by Eric Plutzer and colleagues found that of their sampled high school and middle school teachers, around 75% spent at least an hour per academic year on climate change (87% of high school biology and 70% of middle school science teachers) [5]. Plutzer and colleagues note that this small amount of time dedicated is worrisome by itself, but the quality of education is cause for more concern. Thirty percent of teachers emphasized that recent rises in climate were due to “natural causes” and 12% failed to emphasize human causes. Strangely, 31% admitted to teaching that recent climate change is caused by human activity, but also that many scientists believe it is due to natural causes [5]. Plutzer and colleagues stipulate it may be an attempt to convey both sides of the argument. This is alarming when coupled with the fact that 97% of climate scientists agree that humans are causing global warming and climate change. According to NASA, “international and U.S. science academies, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and a whole host of reputable scientific bodies around the world” have expressed this fact [6].

Sarah B. Wise, a professor at University of Colorado Boulder, conducted a similar study earlier, though limited the sample to Colorado public school teachers. Wise found that while 87% of teachers addressed climate change, the method was much more variable as indicated by a free-response section. According to Wise, many teachers only have an “informal discussion” rather than an organized lecture. Meanwhile, among those that did include a formal lesson plan, more than ⅔ of them indicated the lesson was mainly on “emphasizing the ‘nature of science’ (e.g., how scientists gather evidence, arrive at explanations, and engage in peer review) … and acknowledging or discussing the presence of public controversy and skepticism around the topic of global warming” [7]. These methods of teaching climate change often give way to imagining holes in the idea that humans are responsible for climate change. For example, if a student hears the notion that some scientists disagree on climate change, and the nature of science requires us to have skepticism, their perception of climate change being driven by humans weakens.

While many teachers make sure to emphasize the scientific consensus, the fact that the number is only 54% should be cause for concern.

While many teachers make sure to emphasize the scientific consensus, the fact that the number is only 54% should be cause for concern.

Why is climate change taught this way?

Plutzer and colleagues suggested that teachers may cover certain aspects of climate change and avoid others due to misinformation in their own lives. While 97% of scientists agree that human activity has been responsible for climate change, the public perception of climate change scientists’ knowledge is poor. According to a 2016 Pew Research poll, only 33% of Americans believe climate change scientists understand whether climate change is occurring or not, 28% believe scientists understand the causes, and 27% believe scientists agree that it is caused by humans [8].

When teachers were asked directly in Wise’s study, answers were a bit nebulous. The vast majority reported that a discussion of climate change would not “fit into their curriculum or standards” for various reasons, some being a lack of time, and others citing a limitation of the curriculum itself. Interestingly, unlike a subject such as evolution, very few teachers indicated they felt pressure to avoid teaching the subject by a student or member of the community. Even when teachers were directly discouraged from teaching the subject, free responses indicated it did not affect their decision to include it in the class, through an informal discussion or otherwise.

That being said, the political aspect of climate change should not be ignored. While the extent of the politicization of climate change is a somewhat complicated issue, it is undeniable that many believe climate change is a political subject, and like all political views, it is important to share “both sides” in school. While teachers were found to generally teach climate change, as discussed prior, the discrepancy was with whether they would emphasize human activity or natural causes as the main driving factor. While scientists have recognized there are patterns of climate change that occur naturally, it is also clear that after the mid-twentieth century, when cars became a family staple and humans started producing more greenhouse gas emissions, temperatures spiked much higher than they ever did naturally [9]. It is therefore commonly agreed that in the past few years, human beings are the ones mainly responsible for the increase in temperature.

Wise found that 85% believed teaching both sides was important. When asked why, 25% of teachers said it was because both views held scientific validity and 50% said it was to promote “critical thinking” and “independent decision-making.” Only 25% believed students should learn both, but school curricula should emphasize the scientific consensus that human activity is the driving force [7].

When they asked similar questions to their sample, Plutzer and colleagues found that those who believed it’s “not the government’s business to protect people from themselves” were also most willing to teach both sides [5]. In this sense, Plutzer and colleagues claimed the issue was based more on personal values of the teachers than any formalized curricula that may have been forced onto them.

What needs to be changed

It is clear that education on climate change in America must be made more robust; not only must climate change be required in school curriculums, but it should also emphasize the fact that there is a scientific consensus that human activity is the main cause. Climate change must be standardized at the state level, or at the very least, be mandated to teach. Until there is an established curriculum for climate change, the way it is presented will remain up to teachers.

While some might argue a solution is to educate teachers and allow them to retain power over the way climate change is taught, because of the personal motivations at play, Plutzer and colleagues do not believe this would solve the issue [5]. In an interview with Time Magazine, Plutzer said, “The goal of climate skeptics is very similar to the goals of evolution skeptics. They’re not attempting to prove their point; they’re merely hoping to raise doubt — enough doubt to delay [changes to education] policies” [10].

Instead, Plutzer and colleagues suggest the process of educating teachers will need to draw on science communication research, and specifically help science teachers “acknowledge resistance to accepting the science and addressing its root causes.” A failure to approach educators properly may actually lead to the strengthening of views that seek to teach both sides equally [5].

Until personal biases in teachers regarding climate change can be resolved, some researchers have turned towards extracurricular activities and games to increase climate change knowledge and bridge the partisan gap. Juliette Rooney-Varga and colleagues created a simulation for secondary (grades 6-12) and post-secondary students in which participants role-play as UN delegates who are tasked with saving the world from climate change. The researchers found that of the 2042 participants, 81% reported an increase in their desire to “combat climate change.” In particular, they pointed out the effectiveness in convincing Americans who were “somewhat or strongly opposed to free-market regulation.” This label applied to 40% of all participants, who, prior to the study, indicated lower beliefs “that climate change is caused by human activities,” “lower levels of knowledge about CO2 accumulation dynamics,” and lower levels of “a sense of Urgency” [11]. After the study, their views on climate change “showed no statistically significant differences” when compared to their fellow Americans who favored government regulation.

Similar to how schools still face difficulties teaching evolution, it is unclear exactly how much resistance teachers, schools, and textbook authors will face when incorporating a stronger climate change curriculum into K-12 education. However, with the help of educators and researchers with a desire to foster better science communication, the next generation of students may be better equipped to address climate change in society.

References:

- NASA. The Causes of Climate Change. Accessed January 30, 2022. Available from: https://climate.nasa.gov/causes/

- World population review. Carbon footprint by country. Accessed Jan 30, 2022. Available from: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/carbon-footprint-by-country

- Johnson S. October 18, 2019. Teachers and students push for climate change education in California. Ed source. https://edsource.org/2019/teachers-and-students-push-for-climate-change-education-in-california/618239

- U.S. Department of Education. The Federal Role in Education. Accessed January 30, 2022. Available from: https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/fed/role.html

- Plutzer E, Mccaffrey M, Hannah AL, Rose J, Berbeco N, Reid AH. February 12, 2016. Climate confusion among U.S. teachers. Science. 351(6274):. 664-665. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aab3907

- NASA. Do scientists agree on climate change? Accessed January 30, 2022. Available from: https://climate.nasa.gov/faq/17/do-scientists-agree-on-climate-change/

- Wise SB. January 31, 2018. Climate Change in the Classroom: Patterns, Motivations, and Barriers to Instruction Among Colorado Science Teachers. Journal of Geoscience Education. 58(5): 297-309. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.5408/1.3559695

- Pew Research Center. October 4, 2016. Public views on climate change and climate scientists. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2016/10/04/public-views-on-climate-change-and-climate-scientists/

- Denchak M, Turrentine J. September 1, 2021. Global Climate Change: What You Need to Know. Natural Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/global-climate-change-what-you-need-know

- Worland J. February 11, 2016. Why U.S. Science Teachers Struggle to Teach Climate Change. Time. https://time.com/4214388/science-teachers-climate-change/

- Rooney-Varga JN, Sterman JD, Fracassi E, Franck T, Kapmeier F, Kurker V, Johnston E, Jones AP, Rath K. August 30, 2018. Combining role-play with interactive simulation to motivate informed climate action: Evidence from the World Climate simulation. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0202877. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0202877