By Anjali Borad, Psychology ‘21

Author’s Note: This paper explores the dynamic relationship between a mother and her son and the complexity of a health condition that the son has. I will look at a specific case of cerebral palsy—my brother—and talk about how his condition came to be and the likely prognosis. I want to delve into the details of how family dynamics play a very important role in the caregiving and caretaking that goes along with having a disabled family member and how that is seen in the relationship between my brother and my mother.

I see two different perspectives of my brother, Sam, and his condition, cerebral palsy: one through his eyes and the other through the eyes of my mother, his caregiver. Observing how my mother has taken care of Sam from the beginning, I began to realize that it takes a lot to be a caregiver and that she plays a significant role in his life. In order to gain more insight into her practices of giving care, I interviewed her. I started off by asking her what it means to be a caregiver and what “care” means to her. She took a deep breath in and expressed her daily routines as a caregiver. “Waking up in the morning, the first thing that you have to do is to attend to him and care for him before yourself,” she said. “You know that from brushing his teeth to giving him a shower and feeding him, we have to do everything from A to Z.”[1] A day in the life of my mother starts and ends with my brother, from getting him out of bed to providing him with basic needs like food and water. She even takes care of specific requests that pertain to his own interests, such as wearing a watch every day and having matching socks and pants.

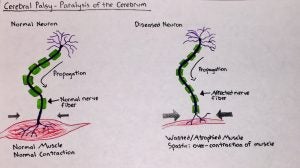

Cerebral palsy is a neurological disorder. Most cases of cerebral palsy occur under hypoxic conditions during the birthing process. This lack of oxygen to the brain can cause developmental delays and lifelong debilitating conditions [2]. My family and I have experienced the difficulties and limitations that accompany this disease first hand. My brother’s condition of cerebral palsy is in its most extreme form: he has quadriplegia and spasticity. A telltale sign of quadriplegic cerebral palsy is the inability to voluntarily control and use the extremities. Spasticity occurs due to a lesion in the upper motor neuron, located in the brain and spinal cord. It interferes with the signals that your muscles need to move and manifests in the body by increasing muscle tone and making the muscles unusually tight [3]. Dr. Neil Lava, a member of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and American Academy of Neurology, describes the pathophysiology of a lack of muscular activity. “When your muscles don’t move for a long time, they become weak and stiff,” Lava writes [4]. This physical restraint is evident in my brother’s case because he has been wheelchair-bound since the age of seven.

Upper motor neuron lesions can worsen over time. Major prolonged symptoms include over-responsive reflexes, weakness in the extensor muscles, and slow movement of the body, all of which affect the sensation of balance and coordination. For this kind of condition, occupational and physical therapy can alleviate some of the symptomatic stresses. In the case of therapy, performing the right kind of stretches can help to relax some muscle stiffness. Medication and certain surgical procedures can also treat upper motor neuron symptoms. Some common muscle relaxants prescribed to patients are Zanaflex, Klonopin and Baclofen [5].

At the neurochemical level, “Spasticity results from an inadequate release of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system,” according to Mohammed Jan [6]. In a normal neural cell, when GABA interacts with and binds to GABA receptors on the postsynaptic neuron, it decreases the likelihood that the postsynaptic neuron will fire an action potential because of the inhibitory nature of GABA receptors. For a condition like cerebral palsy in which some form of insult or damage has occurred to the brain, especially in the upper motor neurons, the result is hyperactive reflexes (as opposed to the calming sensation). At this point, muscle spasticity begins to become detectable. [6]

Apart from the biological mechanism underlying this condition, particularly significant environmental factors also gravely contributed to Sam’s condition. For eight months, my mother was carrying a normally developing fetus in the womb. However, a few weeks before Sam’s delivery date, my mother could not feel any fetal movement for about three days, so she went to check on it. As she was receiving the examination, Sam unexpectedly made a fluttering movement. If he had not moved, my mother would have had to get a Caesarean section immediately. Since he moved inside, the examiners found nothing to be wrong with the fetus and deemed it safe to send my mother home.

Just a few days later, my mom was rushed to the hospital after her labor pain started. At the time, the primary medical staff mostly consisted of medical interns still honing in on decision-making skills during critical situations. From the time of my mother’s arrival at the hospital, 13 hours passed before a team of doctors and interns determined that she needed a C-section. Once this decision was made, additional time was required by the medical professionals to prepare the room for surgery. All the while, my mom was in labor pain and, unbeknownst to her, the fetus had become separated from the placenta while the umbilical cord suffered damage. By the time the surgery finally ended, Sam had suffered from asphyxiation. According to the Cerebral Palsy Guide, “asphyxiation that occurs during labor or delivery may have been caused by medical malpractice or neglect. Early detachment of the placenta, a ruptured uterus during birth or the umbilical cord getting pinched in a way that restricts blood flow can cause oxygen deprivation.” [7]

The most important aspect of a disease, once established and diagnosed, is treatment and therapy. Asking questions about how to manage pain, how to make daily routines easier to perform, and how to accommodate family members in raising a child with a disability all goes into the planning process of treatment as well. These individuals need more than mere pills in order to get through their daily lives. This is where therapists (i.e. occupational, behavioral, speech, physical, and vocational therapists) and related health advocates, including family members, come into play. While therapists cannot completely remove the condition, they provide a strategy to alleviate psychological symptoms, including feelings of loneliness, fear of who will care for you, or resentment towards oneself. Family psychologists can help children with cerebral palsy by providing an initial assessment in an attempt to gain more insight into the family dynamics. If there seems to be a lack of parental support or lack of child attachment, a family psychologist can address this through therapy sessions with the parents. Therapy sessions allow for parents to individually discuss what they think is working well for the child and other areas that can be improved. The parents are also free to talk about their own personal issues, permitting the psychologist to gain a better understanding of certain triggers for the parents. These triggers can affect caregiving for the child with special needs.

Cerebral palsy is more than just a neurological condition. It is a way of life that, for Sam, is entangled in a web of personal, social, familial, caregiver and medical challenges. One noteworthy concept heavily emphasized in the healthcare field today is the importance of a family-centered management model. The notion of a family-centered approach strives to improve the way of life for individuals with the condition in the family in a mutual way. For a family, it can be quite taxing physically and emotionally to have to take care of someone for the rest of their lives. While it is considerably easier for the receiver to reap the benefits of the caregiver, it is more difficult for the caregiver to constantly provide. The family-centered approach tries to find a middle ground where the caregiver or family and the care-receiver are benefitting from each other as much as possible. In a holistic family-centered model, the needs of each family member are taken into consideration.

A study by Susanne King details the role of pediatric neurologists, therapists, and family members, especially parents, in caring for children with cerebral palsy. This study mainly emphasizes the limiting restraints cerebral palsy places on individuals. For example, families with special needs children often have specific ways of communicating, specialized equipment used at home, and a support system consisting of the family members, therapists, and guidance counselors. The heavy emphasis on familial involvement with medical guidance from professionals is the root of family-centered care. King describes that “these children often have complex long-term needs that are best addressed by a family-centered service delivery model.”[8] Oftentimes, we see that those families who have disabled family members are suffering. Some parents, for example, experience great distress because they do not completely understand what is happening to their child and, thus, fail to acknowledge their limitations at times. Others feel that they are incapable of looking after their child but cannot bear the idea of sending them away to an institution.

King also discusses the lack of investigation of families as a whole practicing care-giving. “Although there is much evidence supporting a family-centered approach in the area of parental outcomes, there has been little work reported on the family unit as a whole,” King writes. “The most common outcome is better psychological well-being for mothers (because they generally were the participants in most of the studies).”[8]

In my family, I can actively see family-centered management of my brother’s condition occurring. I see how both my parents have certain roles in my brother’s life that collectively enable or mobilize him to feel included and respected. I like to call my parents the arms and legs for my brother in a figurative sense, and I like to call myself the eyes for my brother. Working together to the best of our ability, we enable him to see the outside world in a way that’s similar to the way we experience it.

All my life, I have seen my mother perform the role of a caregiver. I have seen so many ups and downs in her situation, and I would always ask myself the following questions. What makes her get up every morning and continue to give the care she does? What makes her not give up? She told me, “I have faith in God, and I know that He creates pathways for me to deal with the physical implications of taking care of a disabled family member and see, I have never had any major problems with your brother. I will continue to give care for as long as my body will allow for me to do so.”[1] Annemarie Mol and John Law of Duke University collaboratively published a research paper detailing how people are more than just the definitions of their disorders or conditions. According to Mol and Law, people actively create and construct their life in a way that either enhances or minimizes the intensity of their conditions. Mol and Law also explain that “there are boundaries around the body we do…so long as it does not disintegrate, the body-we-do hangs together. It is full of tensions, however.”[9] Their conclusion on what makes a person pull through encapsulates the reason my mother still continues to care for my brother.

The definition of cerebral palsy as a condition is very limited. Oftentimes people who have debilitating conditions are missing a network or a support system of people, that once established, can essentially improve that family member’s way of life. With the family-centered approach to managing care, one is essentially enabling the disabled family member by actively being a part of their life, including their day-to-day life activities. For example, through the support system we provide for Sam, he can feel that he is in good hands and that he has established emotional and personal security. Although his condition is permanent, it is comforting to know that our family dynamics allow for an environment in which he can thrive while remaining mentally healthy.

References

- Borad, Geeta. “Practices of Care, Interviews.” 8 Dec. 2018.

- Debello, William, and Lauren Liets. “Motor Systems.” Lecture, NPB 101, Davis, CA, 20 Jan. 2020.

- Emos MC, Rosner J. Neuroanatomy, Upper Motor Nerve Signs. [Updated 9 Apr. 2020]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 January. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK541082/

- Lava, Neil. “Upper Motor Neuron Lesions: What They Are, Treatment.” WebMD, 11 May 2018, https://www.webmd.com/multiple-sclerosis/upper-motor-neuron-lesions-overview#1.

- Chang, Eric et al. (2013). “A Review of Spasticity Treatments: Pharmacological and Interventional Approaches.” Critical reviews in physical and rehabilitation medicine vol. 25, 1-2: 11-22.

- Jan, Mohammed M S. (2006). “Cerebral palsy: comprehensive review and update.” Annals of Saudi Medicine. vol. 26, 2.

- Cerebral Palsy Guide. “Causes of Cerebral Palsy – What Causes CP.” Cerebral Palsy Guide. 21 Jan. 2017, https://www.cerebralpalsyguide.com/cerebral-palsy/causes/.

- King S, Teplicky R, King G, Rosenbaum P. (2004). “Family-centered service for children with cerebral palsy and the families: a review of the literature.” Semin Pediatr Neurol. Science Direct.

- Mol, A & Law, J. (2004). “Embodied Action, Enacted Bodies: the Example of Hypoglycaemia.” Body & Society, 43–62.