Amoebiasis, amoebic dysentery, amebiasis, or entamoebiasis: different words for the same disease

Introduction

Amoebiasis is one of the leading causes of death from parasitic disease worldwide, but it is rarely heard about in the United States. The disease is caused by a protist (eukaryotic organisms that are neither animal, land plant, or fungus), specifically an amoebozoa named Entamoeba histolytica. Infection by this parasite is most common in underdeveloped countries and invades hosts by the fecal-oral route, secreting enzymes and using its pseudopods to tear apart human cells in the gastrointestinal tract. In some cases, they can penetrate the gut lining and migrate through the bloodstream to other vital organs. This can lead to bloody diarrhea, as well as abscesses in the liver, lungs, or brain, which may ultimately result in death. Not to be confused with Entamoeba dispar, which is usually commensal and harmless to us [1], Entamoeba histolytica is often overlooked and misdiagnosed, especially in countries with little clean water and medical care.

Epidemiology

Life Cycle/Fecal-Oral Transmission

E. histolytica, a parasitic amoeba, follows a complex life cycle that hinges on the fecal-oral route of transmission. The journey begins when mature cysts are ingested, typically through contaminated food or water. Once inside the small intestine, these cysts release trophozoites, which then colonize the large intestine. Here, they multiply by binary fission, thriving on intestinal bacteria and other contents. In some cases, these trophozoites penetrate the intestinal lining, causing tissue damage and bloody diarrhea. They may even spread to other organs through the bloodstream, leading to abscesses in the liver, lungs, or brain, and potentially, death. Eventually, some trophozoites transform back into cysts within the large intestine, which are then excreted in feces. Poor sanitation leads to contamination of the environment, perpetuating the cycle.

Accurate identification of E. histolytica is crucial in understanding its epidemiology and controlling its spread. However, this is complicated by the morphological similarity between E. histolytica and non-pathogenic species like E. dispar. Traditional microscopy often leads to misdiagnosis, highlighting the need for advanced molecular techniques. DNA-based methods like PCR and dot blot assays have proven to be more effective in differentiating between Entamoeba species, leading to more accurate diagnoses and a better understanding of the parasite's true prevalence [2].

Risk factors

Nath and their research team in India reported that school children and day laborers were most at risk, compared to government workers. This can be attributed to their consumption of street food, the preparation of which often lacks proper hygiene. Lower education levels and poverty, which limit access to health education and proper sanitation, were intricately linked to this risk. Higher rates of E. histolytica infection are seen in asymptomatic individuals compared to symptomatic ones, as asymptomatic individuals often remain undiagnosed and untreated, unknowingly contributing to the spread of the parasite.

Clinical signs

Asymptomatic Colonization

While an estimated 90% of E. histolytica infections are asymptomatic, these carriers can still unknowingly transmit the parasite to others. E. histolytica exists as a cyst (a dormant, protective form) before infecting its host. This cyst form can survive in contaminated water, on food, or on fomites (inanimate objects that can carry infectious agents). Once ingested, the cyst undergoes excystation (a process of shedding its protective wall) in the host's gut, releasing multiple trophozoites (the active, feeding stage of the parasite) [2].

These trophozoites then begin to damage the host's gastrointestinal cells through phagocytosis (engulfing and digesting cells) and trogocytosis (taking bites of cells). Despite this cellular damage, most infections do not trigger a long-term immune response due to the amoeba's ability to evade the host's complement system (a part of the immune system that helps destroy pathogens). E. histolytica achieves this evasion by stealing complement regulatory proteins from host cells and displaying them on its own surface, effectively disguising itself from the immune system [3].

This ability to remain asymptomatic while causing damage and evading the immune system makes E. histolytica a particularly insidious parasite. Asymptomatic carriers may unknowingly contribute to the spread of the infection, highlighting the importance of accurate diagnosis and treatment to break the chain of transmission.

Colitis/Dysentery

When detected by the immune system, trophozoites can cause colitis (inflammation of the colon) and/or dysentery (severe diarrhea with blood and mucus), which are the most common symptomatic responses to E. histolytica infection. Symptoms such as stomach cramps and diarrhea can indicate amoebiasis in patients [5]. Trophozoites adhere to the colon lining (epithelium) using a sugar-binding molecule (lectin) that recognizes specific sugars (galactose and N-acetyl D-galactosamine) on the surface of the colon cells. This attachment allows them to damage the lining and potentially spread to other organs (extraintestinal amoebiasis) [6].

Extraintestinal amoebiasis

The most common extraintestinal amoebiasis is amoebic liver abscess (ALA). Clinical presentations of ALA vary and usually do not have the same symptoms as amoebic colitis [7]. Symptoms include fever, pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, bloody diarrhea, and weight loss. Coughing and right-sided pleural pain are also common. Anemia and hypoalbuminemia are also symptoms of ALA. Pulmonary amoebiasis is the second most common form of extraintestinal amoebiasis. These are spread by the lymphatic system or by hematogenous spread from intestinal lesions. The right lower lobe, nearest the liver, is the most affected area [5].

Diagnosis

Laboratory findings

Diagnosing amoebiasis requires a multi-faceted approach, incorporating parasitological, immunological, and molecular techniques. The traditional "gold standard" involves direct microscopic visualization of the parasite in stool, bodily fluids, or tissue samples, proving particularly effective for diagnosing intestinal amoebiasis in symptomatic patients from endemic regions [7]. However, diagnosing extraintestinal amoebiasis, such as ALA, is more challenging due to the lack of concurrent amoebic colitis in most patients and the persistence of IgG antibodies from previous exposure [7].

Consequently, alternative diagnostic strategies are essential for accurately identifying extraintestinal amoebiasis. While imaging techniques like ultrasound, CT, and MRI can detect abscesses, they cannot definitively identify the cause. Newer serological assays targeting specific antigens or antibody subclasses like IgA may offer improved accuracy in diagnosing ALA. Molecular techniques like PCR can identify E. histolytica DNA in various samples, but their availability and cost-effectiveness in endemic regions can be limiting. Antigen detection tests, which detect specific proteins produced by E. histolytica, are also being explored as a potential diagnostic tool for both intestinal and extraintestinal amoebiasis. The development and refinement of these alternative diagnostic strategies are crucial for improving the accuracy and timeliness of diagnosing extraintestinal amoebiasis, ultimately leading to more effective treatment and better patient outcomes.

Microscopic findings

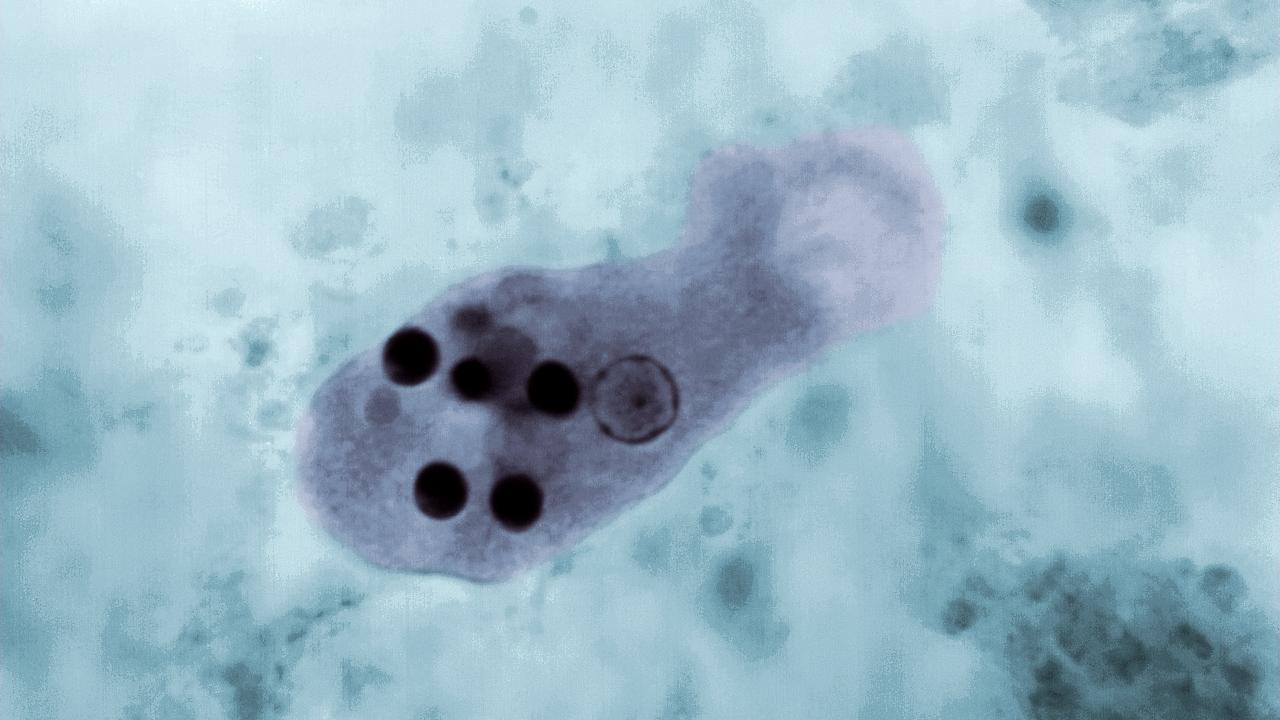

Microscopic examination of stool samples remains a common method for diagnosing amoebiasis, especially in areas with limited resources [7]. This technique directly visualizes the parasite in its cyst or trophozoite stage. However, it has limitations that affect its accuracy. A simple examination of a fresh stool sample with saline solution might not be sensitive enough to detect E. histolytica. To identify motile trophozoites, which can be diagnostic due to the presence of ingested red blood cells, the stool needs to be examined within an hour of collection. Preserving the sample with specific fixatives becomes necessary if immediate examination is not possible. While motile trophozoites are more likely to be found in loose stools with mucus, pus, and traces of blood, cysts can be present in both formed and loose stools. Permanent staining of stool smears allows for better visualization of the parasite's morphology, size, and number of nuclei. However, even though microscopic examination offers a definitive diagnosis by visualizing the parasite itself, it has drawbacks. A significant limitation is the difficulty in differentiating E. histolytica from other morphologically similar amoebas, particularly E. dispar and Entamoeba moshkovskii. This challenge can lead to misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment. Additionally, differentiating these species requires a skilled technician, impacting the overall sensitivity and specificity of this diagnostic method.

Differential diagnosis

Molecular diagnostic tests are increasingly used for detecting amoebiasis due to their high accuracy. These tests involve amplifying specific DNA sequences of the parasite. Several techniques exist, including conventional PCR, real-time PCR, and loop- mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). These methods can differentiate and detect Entamoeba species in stool, tissues, and even liver lesion samples.

One commonly targeted gene is the small subunit ribosomal RNA (rRNA) due to its presence in multiple copies within the parasite. This target allows for sensitive detection and can even differentiate between E. histolytica and the morphologically similar E. dispar due to slight genetic variations in the gene. Studies using this target have successfully identified E. histolytica in stool samples and differentiated it from other intestinal parasites [7].

Treatment

Treatment approaches depend on the severity and location of the infection. Noninvasive colitis cases can be treated with medications like paromomycin that eliminate cysts within the intestinal tract. For invasive amoebiasis or infections outside the intestines, nitroimidazoles (e.g., metronidazole) are the primary therapy. However, these medications only target the active trophozoite stage. Studies indicate that nitroimidazole treatment alone leaves cysts in 40-60% of patients [6]. Following a course of nitroimidazoles, paromomycin is typically administered to eradicate remaining intestinal cysts and prevent relapse. Additional options for eliminating luminal parasites include diiodohydroxyquinoline and diloxanide furoate. Severe cases of amoebic colitis may require broad-spectrum antibiotics to address the risk of bacterial translocation. Surgery is rarely needed but might be considered for patients with signs of a critical abdomen or toxic megacolon. For amoebic liver abscess (ALA), aspiration of the pus may be necessary, particularly if there is no improvement after initial treatment. Drainage is also recommended for patients with high-risk abscesses or large pleural effusions. Imaging-guided techniques like needle aspiration or catheter drainage are the preferred methods for these procedures.

Prevention

Public health efforts to prevent amoebiasis primarily focus on promoting good handwashing and hygiene practices. Studies suggest that proper handwashing with soap and water can significantly reduce diarrheal diseases, including amoebiasis, by up to 50% [6]. This simple yet effective strategy is particularly important after using the toilet, changing diapers, and before handling or preparing food. However, implementing such practices can be challenging in regions with limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities.

About the Author: Aaron Dukes

Aaron, a senior Molecular and Medical Microbiology major at the University of California, Davis, is driven by a passion for global health and infectious disease. His academic journey has led him to the Ralston Lab, where he conducts research on the parasite Entamoeba histolytica and its devastating impact on populations worldwide. Developed for UWP 104E, this paper reflects Aaron's commitment to bridging the gap between research and the medical field. By providing a comprehensive overview of amebiasis – its causes, symptoms, and potential treatments – Aaron aims to raise awareness and inform potential advancements in prevention and care. Beyond his academic pursuits, Aaron previously participated in the EMRAP program, shadowing doctors in emergency rooms and gaining firsthand experience in the medical field. Additionally, he has contributed to conservation efforts in his hometown of Bakersfield by studying the impact of microplastics on the diet of endangered kitfoxes. Looking towards the future, Aaron aspires to a career in virology research, where he can continue to unravel the complexities of viral pathogens and contribute to the development of novel treatments. Ultimately, he envisions transitioning into academia, where he can share his passion for microbiology and inspire the next generation of scientists.

Author's Note

I wrote this piece for my UWP 104E class at UC Davis as a technical explanation for the medical field. I chose this topic because I am currently researching the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica that causes amebiasis at the Ralston Lab at UC Davis. It is a fairly unknown parasite in developed countries but causes a significant number of deaths yearly. I want readers to know about this deadly disease, what causes it, and how we can improve prevention and treatment methods.

References

Stanley SL. 2003. Amoebiasis. Lancet. [accessed 2024 March 20] 361(9362):1025–1034. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9.

Nath J, Ghosh SK, Singha B, Paul J. 2015. Molecular Epidemiology of Amoebiasis: A Cross Sectional Study among North East Indian Population. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. [accessed 2024 March 20] 9(12): e0004225. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004225.

Ximénez C, Morán P, Rojas L, Valadez A, Gómez A, Ramiro M, Cerritos R, González E, Hernández E, Oswaldo P. 2011. Novelties on amoebiasis: a neglected tropical disease. J Glob Infect Dis. [accessed 2024 March 20] 3(2):166–174. doi:10.4103/0974 777X.81695.

Miller HW, Tam TSY, Ralston KS. 2022. Entamoeba histolytica Develops Resistance to Complement Deposition and Lysis after Acquisition of Human Complement-Regulatory Proteins through Trogocytosis. MBio. [accessed 2024 March 20] 13(2): e0316321. doi:10.1128/mbio.03163-21.

Rivero Z, Villareal L, Bracho Á, Prieto C, Villalobos R. 2021. Molecular identification of Entamoeba histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii in children with diarrhea from Maracaibo, Venezuela. Biomedica. [accessed 2024 March 20] 41(Supl. 1):23–34. doi:10.7705/biomedica.5584.

Kantor M, Abrantes A, Estevez A, Schiller A, Torrent J, Gascon J, Hernandez R, Ochner C. 2018. Entamoeba histolytica: updates in clinical manifestation, pathogenesis, and vaccine development. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. [accessed 2024 March 20] 2018:4601420. doi:10.1155/2018/4601420.

Saidin S, Othman N, Noordin R. 2019. Update on laboratory diagnosis of amoebiasis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. [accessed 2024 March 20] 38(1):15–38. doi:10.1007/s10096-0183379-3.