Water Quality, Sanitation, and Waterborne Illnesses in Underserved Rural India

Abstract

India struggles with addressing long-standing water pollution, which has fueled over 37.7 million cases of waterborne illnesses and 1.5 million child deaths. Rural communities especially bear the brunt of this crisis due to limited resources. Tackling this multifaceted issue extends beyond mere technical solutions and requires mindfulness of the culture in rural India. This problem, beyond its scientific dimensions, is fundamentally ethical and requires sustainable solutions such as plant xylem-based and biosand water filters. These solutions take into account the circumstances of the vulnerable populations and aim to use materials that can be locally sourced and are inexpensive. By understanding the intricate link between water quality, sanitation, hygiene practices, and waterborne diseases like dysentery in underserved regions, we can develop cost-effective, sustainable interventions to enhance human health in these areas, addressing the immediate crisis and creating a positive impact on the long-term well-being of rural India.

Introduction

As the most populated country in the world, India faces a challenge in ensuring access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation facilities for its diverse population. As India’s population rises, so does the frequency of contamination, poor waste management, absence of sanitation, and open defecation practices. The Indian government has attempted to mitigate their consequences through laws such as the Water Prevention and Control of Pollution Act of 1974, but enforcement in public-sector enterprises has been largely unsuccessful. In rural settings, this has led to a lack of infrastructure to support proper sanitation, racketeering of clean water sources by organized crime (forcing entire communities to survive off polluted water), and gaps in proper hygiene education. As a consequence, preventable waterborne illnesses are spreading at a staggering rate: millions of cases of both severe and lethal waterborne illnesses are reported every year, many infections killing countless children and adults alike [1]. Thus, clean water and proper sanitation are essential factors for preventing public health crises. Addressing this crisis remains difficult due to a significant gap in our understanding of how to formulate effective and targeted interventions for the specific factors contributing to waterborne illnesses in rural areas of India.

This review outlines what is currently understood about the relationship between water quality, sanitation, and hygiene in rural India and its impact on waterborne illnesses. It will explore challenges in water quality, sanitation infrastructure, hygiene practices, discuss the spectrum of waterborne illnesses commonly found in rural areas, and outline effective interventions. For the purpose of this review, “water quality” refers to the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of water that determine its suitability for specific uses, including drinking, agriculture, and industrial processes. It involves factors such as the presence of contaminants, pathogens, and pollutants that may make the water unsafe for consumption. Additionally, “sanitation” in the context of this review refers to both facilities and services for the safe disposal of human waste and the promotion of hygiene practices. It plays a critical role in preventing the contamination of water sources and the spread of waterborne diseases. These practices act as a safeguard, ensuring the protection of water sources and decreasing the transmission of waterborne diseases, contributing to the overall health and well-being of communities.

Waterborne diseases in rural India

Waterborne diseases disproportionately affect rural communities in India [2]. These illnesses encompass a spectrum of infections, but one of the most prevalent and impactful is dysentery. Caused by various bacterial and protozoan pathogens, this condition induces severe symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and dehydration. It poses a heightened risk to the elderly, whose immune systems are weakened by age, increasing the likelihood of severe complications that may ultimately lead to death. Even diseases not as severe as dysentery impose economic burdens through medical expenses and lost productivity, perpetuating the cycle of poverty.

Another widespread disease is hepatitis, specifically Hepatitis A (HAV) and E (HEV) . Unlike other forms, HAV doesn't result in chronic liver disease but can cause acute liver inflammation. This leads to symptoms like jaundice (abnormal yellowing of skin and eyes), fatigue, and abdominal pain. The virus hits particularly hard on vulnerable populations due to factors like inadequate sanitation, contaminated water supplies, overcrowded living, limited access to healthcare services, and socioeconomic challenges. HEV, responsible for a significant portion of sporadic acute viral hepatitis cases in India, mainly affects young adults and can lead to outbreaks through contaminated water supplies. Moreover, the co-infection of HAV and HEV raises questions about the evolving nature of these viruses, suggesting shifts in transmission routes or even diagnostic methodologies. This underscores the need for a preventative approach to address waterborne diseases to cover for the dynamic nature of such infections [3].

Access to clean water and water quality

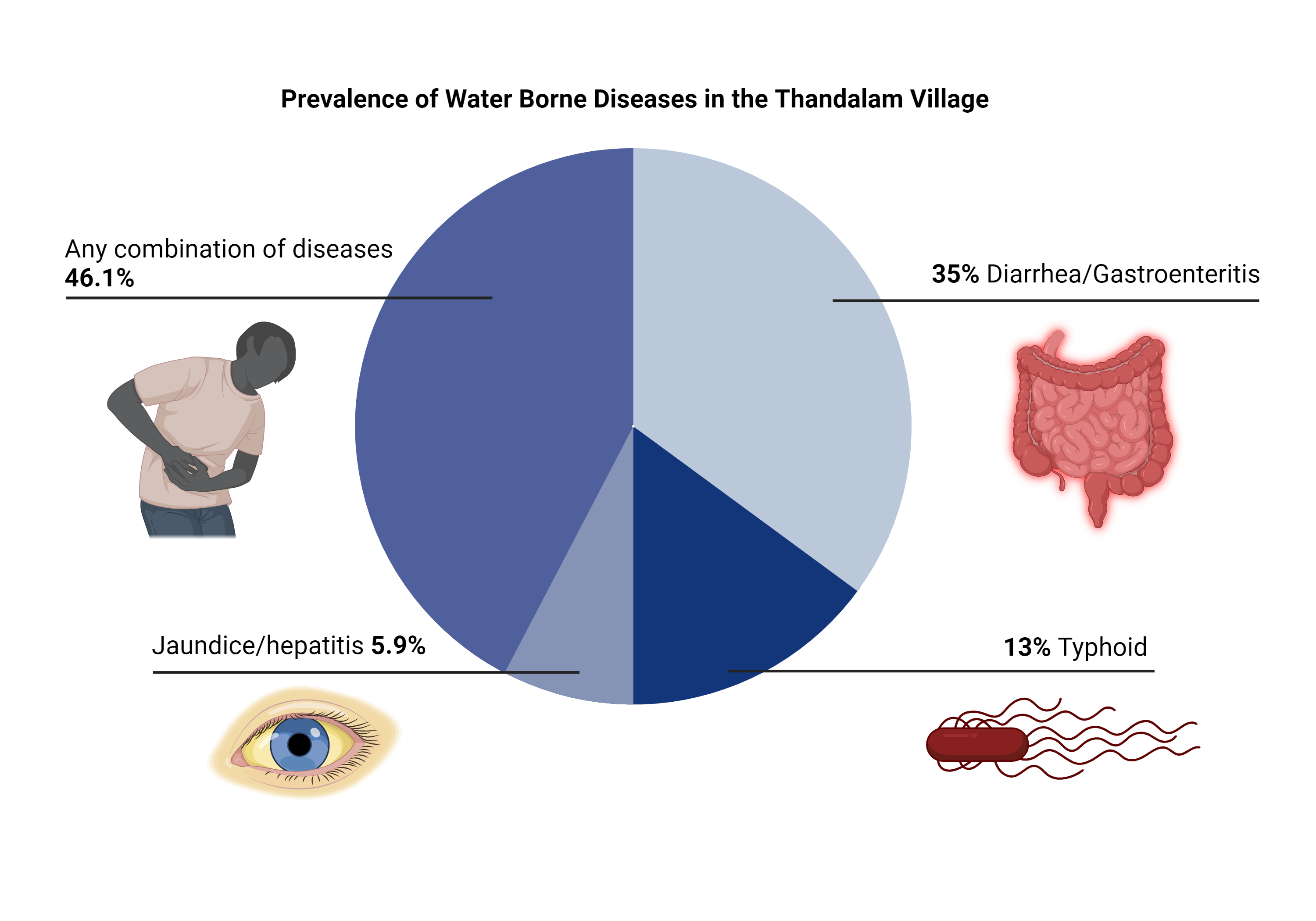

Access to clean and safe drinking water is a fundamental human right, yet 600 million people in rural India grapple with the scarcity of reliable sources of clean water [4]. Most rural communities primarily depend on sources such as public taps and tube wells. These are prone to contamination, as the infrastructure is scarcely cleaned and often directly pumping unfiltered surface water. They are also not reliable, as one-fifth of communities that use them still experience biannual water scarcity, sometimes enduring 2-3 days without access to any water source at a time [4]. This forces many to choose between risking their health on unsafe alternatives or falling deeper into poverty by buying clean water from organized criminals at gouged prices (as much as $50 per kiloliter). Kuberan et al. (2015) examined the water quality in rural areas and how much villages invested in their water quality. They did this through a cross-sectional study surveying head members of 100 randomly selected households in Thandalam village, Chennai. The choice of this specific location for the study is due to its location in Tamil Nadu, a region where more than half of the population resides in rural villages. These included how each family obtained their water, if they had any problems in obtaining them or their quality, how they purify and store water, and any noticeable health concerns linked to water quality. The survey shockingly revealed that 45% of respondents did not treat their water before consumption (even though communities in Chennai primarily rely on potentially contaminated public taps and tube wells), nearly 50% considered their potentially contaminated water safe, and 18% reported suffering from diarrhea due to unclean water consumption [4]. Another study by Biswas et al. (2022) assessed India's progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6), a United Nations plan championed by India to help address access to clean water and sanitation. They found that while India had made improvements, disparities in access to safe drinking water, especially in rural areas, still existed. Approximately 34.1% of households from lower social castes in rural areas had to travel long distances ranging from 200 meters (0.1 miles) to 1.5 kilometers (0.9 miles) to retrieve water [5]. This situation places an immense physical strain on individuals, especially women and children who are often tasked with this responsibility, leading to physical injuries and long-term health issues. Moreover, the time-consuming nature of water collection detracts from income-generating work, deepening poverty.

Sanitation facilities

Although poor water quality has significantly increased the introduction of waterborne illnesses, inadequate sanitation facilities are also responsible for their proliferation. Sanitation plays a pivotal role in preventing contamination of water sources through safe waste disposal practices. Additionally, proper sanitation facilities and practices, such as the use of clean toilets and avoidance of open defecation, lower the direct introduction of fecal matter into the environment. Effective sanitation not only safeguards water sources from contamination, but also fosters community health. In the long term, it reduces healthcare expenses and enhances overall well-being, making sanitation an essential component to public health.

In rural India, inadequate access to sanitation facilities remains a deeply entrenched issue. Biswas et al. (2022) identified stark inequality between Indian regions partly due to issues with government-subsidized latrines (public toilet facilities): their success excelled in northeastern states like Assam, while use in southern states like Tamil Nadu fell below the national average [5]. M.R. (2021) similarly found from secondary data in surveys by the World Health Organization, UNICEF, and the Indian government’s National Sample Survey, that higher-caste individuals from urban areas had access to sanitation facilities 91.2% of the time compared to 56.6% for lower-caste rural individuals. Additionally, they saw that despite India's attempt to reduce open defecation by expanding latrines, concerns still linger over their quality. Government latrines often lacked walls or roofs. While open defecation also poses challenges to privacy, the issue with government latrines adds an extra layer of discomfort. In the case of open defecation, individuals may have outdoor spaces where they can maintain some level of privacy. However, the poorly constructed latrines not only fail to provide a private environment but also expose users to the gaze of others within the confined space. Many, especially women, found this absence of privacy deeply intrusive. The study concluded that to improve sanitation policy, addressing the social context influencing defecation choices and latrine acceptance is crucial [6]. Collaboration between central and local governments is imperative for meeting human needs while preventing illness through improved access to clean water.

Kumar et al. (2022) also help quantify this through seniors’ data from the national 2017-2018 Longitudinal Ageing Study in India. The study assessed 31,464 individuals from rural and urban areas and explored variables like age, toilet facilities, water sources, and region. The study revealed substantial disparities between urban and rural seniors, with rural elders facing higher underweight rates (⅓ of adults in rural areas), limited access to improved sanitation and clean water, and less stable housing with only 4 out of 10 adults living in rural areas living in pucca (solid and permanent) houses. Rural areas exhibited a 10.2% greater prevalence of waterborne diseases among the elderly compared to urban regions. By concentrating on the relationship between malnutrition and infection, Kumar emphasizes the critical role it plays in mitigating waterborne diseases in rural elder populations [7].

Hygiene practices and education in rural India

Despite progress in various aspects of development, there are still widespread challenges related to hygiene. Insufficient access to clean water, coupled with limited awareness about proper hygiene practices, contribute to the persistence of preventable diseases. A lack of poor personal hygiene was noted in Kuberan et al. (2015)’s survey of rural communities in Chennai. The researchers used a questionnaire targeted at adults aged 18 and above. They collected data on their sociodemographic profile and assessed their knowledge, attitude, and practices concerning drinking water and sanitation. They found that 32% of individuals expressed no need for handwashing after using the toilet, though 49% also acknowledged the potential benefits of comprehensive hygiene education [4]. This contextualizes the benefits rural areas would gain from proper hand-washing education and the desire communities express for it.

Benefits of education are quantified by the education results in Kumar et al. (2022). The authors focused on general school education, reasoning that typical curricula raise one’s awareness about disease spread and thereby increase consciousness about personal hygiene. Using adjusted odds ratios, which quantify individual correlations between multiple variables, they found that the risk of waterborne diseases decreased with increasing education levels. Seniors without primary education were on average 56% more likely than those with postsecondary education to contract waterborne diseases, which decreased to 37% with primary education and then 31% with secondary education. This association was telltale in the rural-urban divide: 15% of urban seniors had postsecondary education compared to only 3% in rural areas; rural elderly likewise experienced a 10.2% greater prevalence of waterborne diseases than urban elderly [7]. While it is important to note that other socioeconomic factors held a significant influence on the infection disparity–the study also found only a third of rural elderly had access to improved toilet facilities compared to 90% in urban elderly [7]–the trend demonstrates a pivotal role of general education in shaping hygiene practices and reducing waterborne disease prevalence [4, 5]. Education not only empowers individuals with knowledge but also fosters awareness of the risks associated with poor water and sanitation practices.

Sustainable solutions for mitigating the water crisis

Past methods and why they have not worked

Addressing the water quality and sanitation challenges in rural India requires affordable and scalable solutions. Numerous other strategies alongside the aforementioned sanitation facilities have been attempted in the past, but fell short of meeting what this review will call the FAS criteria: feasibility, scalability, and affordability. For instance, point-of-use water treatment methods like chlorine tablets, which cost 2,490.38 rupees for a small pack (around $30), face limited impact due to costliness for rural households. Similarly, the effectiveness of rainwater harvesting systems is hampered by India’s monsoons, which bring cycles of prolonged dry spells. Hand pumps to extract groundwater and piped water supply projects failed to prevent contamination and are expensive to maintain. Lastly, public education campaigns to promote hygiene awareness face barriers like low literacy rates and cultural resistance to change [4]. These collective experiences emphasize the urgent need for a more holistic, community-driven solution that accounts for local conditions and challenges to effectively address water and sanitation issues in rural India.

Cost-effective solutions

To craft a solution to this pressing issue while meeting the FAS criteria, researchers are exploring novel approaches. One approach proposed by Boutilier et al. (2014) involves plant xylem-based ultrafiltration as a cost-effective and sustainable approach to water purification. This technique leverages the natural filtration properties of xylem, particularly pine sapwood, to effectively filter and purify water in resource-constrained rural areas. The mechanism behind xylem-based ultrafiltration is rather straightforward: xylem vessels naturally filter water as it is drawn up through the plant, removing particles and microorganisms. People can replicate this natural filtration process by carefully preparing a section of pine sapwood, which is often sourced from readily available pine branches or trees. This sapwood is then assembled into a filter in the form of a small tube inserted into a larger pipe or container [8].

Contaminated water is introduced into one end of the xylem-based filter, which then travels through the channels within the sapwood. As the water progresses through the wood, the natural filtration properties of the plant material come into play, physically trapping and filtering out microorganisms and particles. What emerges on the other side is significantly cleaner and safer drinking water. Maintenance of the xylem-based filter is also minimal as plant xylem vessels, although not alive, naturally, filter water by trapping particles and microorganisms. Moreover, as pine sapwood is biodegradable and its preparatory tools are readily available in rural areas, this method is highly sustainable. Its cost-effectiveness, simplicity, and reliance on natural processes make plant xylem-based ultrafiltration a promising solution for providing clean and safe drinking water to resource-constrained communities [8].

There are other cost-effective purification methods to choose from as well. A meta-analysis by Venkatesha et al. (2020) examined the cumulative usefulness of 12 purification methods for rural communities in coastal Western India. They scored each method based on their cumulative strengths in several attributes of FAS criteria, effectiveness, sustainability, and social acceptability. The study ultimately ranked the best method to be biosand filtration. Chlorination and coagulation-disinfection tied for a close second; both methods disinfect water as effectively or even better than biosand filtration, but require complicated supply chains and often make water repulsive to drink. Nevertheless, each purification method has its unique profile of advantages and disadvantages that can be tailored to each community based on its resources [9].

Factors for successful integration of solutions

Community involvement is another key component of successful interventions [5]. Engaging local communities, especially in villages with a head leader, in the planning and implementation of water and sanitation projects not only ensures their ownership but also enhances the sustainability of these initiatives. Community members can actively participate in the construction and maintenance of sanitation facilities, fostering a sense of responsibility and long-term commitment.

Local perceptions and cultural factors also play an intricate role in water purification interventions [6, 10]. Perceptions of water safety and taste preferences can affect the adoption of some interventions such as filters and purification methods [10]. Cultural norms around gender roles may also impact the division of labor related to water collection and sanitation responsibilities. Understanding these societal nuances is crucial for designing effective interventions that align with local customs and beliefs.

Sustainability is also a critical aspect of any intervention in rural India [4, 5]. Solutions must be designed with long-term factors in mind, including maintenance, resource availability, and adaptability to changing conditions. Simply put, a one-size-fits-all approach will not work. Rather, we must be able to try and seamlessly implement novel findings and discoveries in a way so rural communities can take pride in their clean water.

Conclusion

The issue of waterborne illness in rural India has long been a neglected area of study. Factors such as water quality, sanitation, and hygiene practices contribute heavily to the prevalence and susceptibility of waterborne illness. With the quality of water slowly declining over recent years, access to clean water is increasingly scarce. Communities in rural India face issues such as poor quality and acceptability of government-subsidized sanitation facilities which in turn fails to discourage open defecation. Hygiene practices are also deficient, with limited awareness of handwashing’s role in preventing diseases. These three interlinked factors—water quality, sanitation, and hygiene—collectively fuel the spread of waterborne illnesses that disproportionately affect rural communities.

There is hope in promising approaches like xylem-based ultrafiltration and bio-sand filtration, which offer sustainable cost-effective solutions. Implementation of these solutions cannot succeed without societal interventions addressing community involvement and cultural perceptions. By implementing these strategies, India can move closer to the SDG 6 it has championed: the end of waterborne suffering for all.

About the Author: Shivani Chidambaram

Shivani is a class of 2026 Biotechnology major.

Author's Note

From the beginning, my fascination with global healthcare propelled me to explore this field more deeply. It was in UWP 104E with Dr. MacArthur, where I was challenged to contemplate meaningful contributions to the field of global health. Through brainstorming, I was brought back to a documentary I watched years ago, Slingshot. The documentary tells the story of Dean Kamen, an inventor whose mission to address the global clean water crisis led to the creation of the Slingshot water purification system. The film showed the disparity between water abundance in some regions and the harsh reality faced by communities worldwide lacking access to this fundamental human right.

Taking inspiration from Kamen, I decided to utilize my writing skills to raise awareness about the water crisis in India. This literature review aims to provide you with a comprehensive understanding of the complexities surrounding India's water crisis, shedding light on potential solutions for rural communities grappling with limited access to clean water. As you read this review, my intent is to arm you with knowledge on the root causes and effective strategies to combat this pressing issue.

Kamen's journey in Slingshot, intertwined with my personal experiences, underscores the belief that armed with knowledge, each of us can significantly contribute to solving even the most daunting global challenges. With this in mind, I encourage you to journey through this literature review, and I hope that you will emerge with a deeper understanding of the water crisis in India and a renewed sense of empowerment to make a positive impact.

References

Mudur, G. (2003). India's Burden of Waterborne Diseases Is Underestimated. BMJ. 326(7393): 1167.

WHO/UNICEF Joint Water Supply, & Sanitation Monitoring Programme. (2015). Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2015 update and MDG assessment. World Health Organization.

Arora, D., Jindal, N., Shukla, R. K., & Bansal, R. (2013). Water Borne Hepatitis A and Hepatitis E in Malwa Region of Punjab, India. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 7(9): 1971-1973.

Kuberan, A., Singh, A. K., Kasav, J. B., Prasad, S., Surapaneni, K. M., Upadhyay, V., & Joshi, A. (2015). Water and sanitation hygiene knowledge, attitude, and practices among household members living in rural settings of India. Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine. 6(2): 224-228.

Biswas, S., Dandapat, B., Alam, A., & Satpati, L. (2022). India’s achievement towards Sustainable Development goal 6 (ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all) in the 2030 agenda. BMC Public Health. 22(1): 135.

M.R., A. (2021). Quality of Drinking Water and Sanitation in India. Sage Journal. 15(1): 7-17.

Kumar, P., Srivastava, S., Banerjee, A., & Banerjee, S. (2022). Prevalence and predictors of water-borne diseases among elderly people in India: Evidence from Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, 2017–18. BMC Public Health. 22(1): 747.

Boutilier, M. S. H., Lee, J., Chambers, V., Venkatesh, V., & Karnik, R. (2015). Water filtration using plant xylem. PLoS ONE 9(2):e89934.

Venkatesha, R., Rao, A. B., & Kedare, S. B. (2020). Appropriate household point-of-use water purifier selection template considering a rural case study in western India. Applied Water Science. 10(5): 1-11.

Francis, M. R., Nagarajan, G., Sarkar, R., Mohan, V. R., Kang, G., & Balraj, V. (2015). Perception of drinking water safety and factors influencing acceptance and sustainability of a water quality intervention in rural southern India. BMC Public Health. 15(1): 731.