Early Introduction of Food Allergens in Fetuses and Infants

Abstract

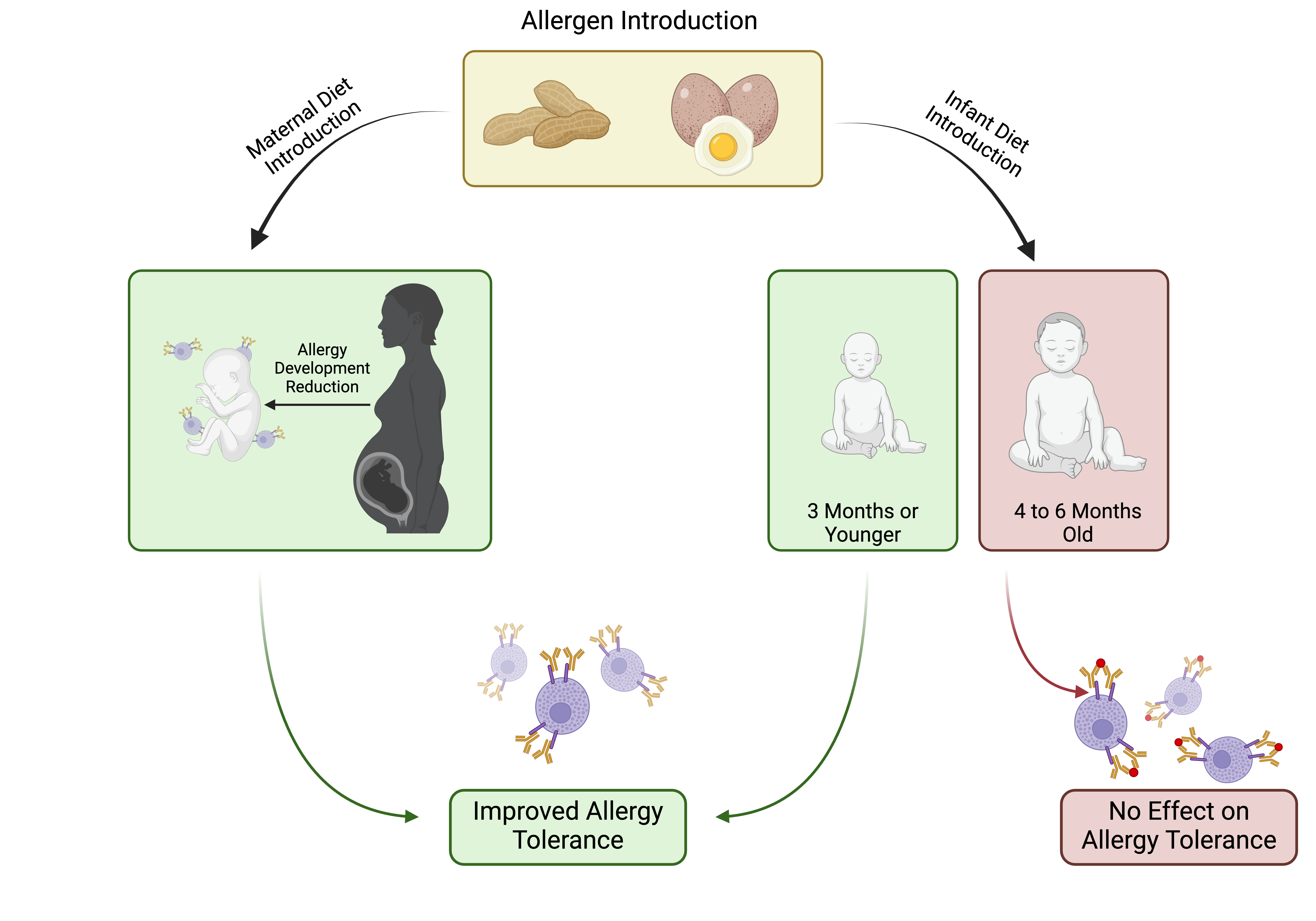

This review aims to explore the efficacies of peanut and egg allergen exposure on allergy reduction in infants compared to fetuses. Research studies were collected from the PubMed and Scopus databases, limiting studies that were case studies or randomized control trials conducted within the past 10 years. Fetal studies could be from any trimester of pregnancy, exploring the outcomes of allergen intake through maternal diet. Infant studies introduced allergens within the first year of life either through direct oral intake or via breastfeeding. Six studies were systematically reviewed, two fetal studies and three infant studies. Both fetal and infant studies supported the introduction of peanuts and eggs to reduce allergic development. Fetal studies indicated no ideal window of time for introduction during pregnancy, instead suggesting consistency in allergen intake. Infant studies point towards introducing food allergens at 3 months or earlier to have preventative effects. Fetal and infant introduction of food allergens (peanuts and eggs) may be preventative in the development of food allergies and some atopic disorders.

Keywords: peripregnancy, peanut allergy, egg allergy, infant, allergen intervention, allergen exposure

Introduction

Food allergies, such as peanut and egg allergies, have been on the rise in recent years and are life-threatening chronic conditions that have a great impact on one’s daily life. According to a 2018 study, 8% of children in the US were determined to have at least one food allergy [1]. Food allergies are the result of the immune system’s IgE antibodies overreacting to certain food proteins, causing various symptoms like hives, shortness of breath, vomiting, and weak pulse. Preventative measures have been studied and tested to reduce the severity of these conditions, given that a significant portion of children with food allergies experience severe reactions. Oral immunotherapy (OIT) is one preventative measure that introduces increasing doses of an allergen to a patient under medical supervision. Its goal is to desensitize patients to their allergen to prevent their immune system from responding so harshly that life-threatening reactions, like anaphylaxis, occur. OIT is usually deployed as a treatment for patients with existing allergies, but the concept can also be applied as preventative measures for children who do not have allergies but are at a high risk of developing them later in life. Common risk factors of the latter include eczema, asthma, and a family history of food allergies. The preventative influence of introducing food allergens is unclear and the recommended period to introduce them is frequently changing [2].

Research has sought to understand the benefits of introducing allergens in different age groups, but studies have yet to be compared to find the ideal window of time for children to be introduced to allergens. This literature review aims to determine whether this window exists in early childhood or the fetal stages to prevent the development of allergies using OIT. It will focus on egg and peanut allergies, which are among the most common childhood allergies, and examine the development of both the allergies themselves and associated atopic disorders like eczema, asthma, and hay fever in infants and fetuses exposed to potential food allergens.

Research Question: In children at risk for food allergy development, how does introducing potential food allergens, like peanuts and eggs, affect the development of food allergies in fetuses compared to in infants?

Methods

Databases and MeSH Terms

This review primarily used studies illustrating outcomes of allergic developments in infants and fetuses who were exposed to potential allergens. Separate studies were searched to address infant outcomes and fetus outcomes to determine if there are more benefits in one demographic than the other. The MeSH terms used to search for papers were “pregnancy”, “allergy immunotherapy”, “peanut allergy”, “egg allergy”, “oral immunotherapy”, “prenatal”, “atopic”, “intervention”, and “infant”. When searching, groupings like “peanut allergy” AND “immunotherapy”, “pregnancy” AND “atopic disorders”, “infant” AND “allergy intervention”, and “allergen exposure” AND “pregnancy” were used to ensure the overlap of topics relevant to the research question. The listed MeSH terms were used in two databases, PubMed and Scopus.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Chosen studies were primarily found using MeSH terms on PubMed and filtering through the results to find papers relevant to the research question. The studies selected were filtered through Scopus and were chosen if they had a Field Weighted Citation Impact (FWCI) score above 1.0 to limit chosen studies to ones highly cited by other researchers. The FWCI score displays the ratio of the study’s citations and the citation number of similar papers published within three years of the selected study. The papers included were randomized control studies and case-control studies exploring the efficacy of early allergy exposure. To ensure research was up to date regarding food allergies, only papers published in the last 10 years (2014-2024). For the fetal introduction of food allergens, studies exploring maternal diet and allergy development or tolerance in the fetus after childbirth was examined. The studies could span from any period during the pregnancy, though the first trimester from week 0 to week 12 was prioritized as that is when the fetus's immune system matures. For infant introduction of food allergens, studies going over ingestion of the allergens via breastfeeding or through direct oral intake of the allergen were used. The infant studies were limited to those that introduced allergens during the first year of life.

Results

Food Allergen Introduction In Fetuses

The introduction of peanuts in fetuses resulted in lower probabilities of the development of atopic disorders and food allergies. Bunyavanich et al. (2014), focusing on the specific allergen introduction of peanuts during the first trimester, concluded that peanut introduction through the mother reduced the likelihood of infant development of peanut allergy [3]. In the study, non-allergic mothers who had single-child pregnancies were selected from the Project Viva cohort of Massachusetts from 1999 to 2002, a pre-birth cohort used to study the influence of diet on early life [3]. The mothers completed a food frequency questionnaire during their pregnancy, and their results were compared to the outcome of atopic disorders (asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis) in the children of the mothers in the study. When comparing the data, daily intake of peanuts during the first trimester resulted in a 47% reduction in the development of mid-childhood peanut allergies compared to no intake. Similar results were found in Frazier et al. (2014), which recorded mothers’ rates of peanut intake during their pregnancies between 1991 and 1995, and the prevalence of allergies in their resulting children in 2006 and 2009. The study observed that non-allergic mothers who ate 5 or more servings per week during their pregnancies bore children with a 69% reduced risk of peanut allergies compared to non-allergenic mothers who ate less than a serving per month [4]. Allergic mothers who consumed 5 or more servings per week of nuts exhibited opposite effects where the consumption of nuts resulted in a 162% increase in risk for peanut allergy development in children. Both studies indicate an inverse correlation between maternal consumption of peanuts during pregnancy and development of peanut allergy development.

Food Allergen Introduction In Infants

Infant introduction to food allergens had conflicting results for studies with chicken eggs, while peanut introduction shared similar results across studies. Bellach et al. (2017) performed a randomized trial for early egg introduction in 383 infants, 4 to 6 months of age, from maternity wards in Berlin, Germany [7]. 199 infants were placed into a control group that received rice powder (placebo) and 184 in an intervention group that received egg powder. The powders were given to the respective groups 3 times a week orally until 12 months of age. After the 6-8 month period of oral intake of the placebo or egg, IgE levels for chicken eggs were measured to determine egg sensitivity, and oral challenges (controlled doses of the egg allergen) were performed to determine if the infants had developed egg allergies. It was found that the oral introduction of eggs in this early time frame had no effect on preventing egg allergies. In fact, some of the infants had already developed a sensitivity to eggs prior to the intervention.

Skejerven et al. (2022) introduced eggs and peanuts at an earlier and longer time frame, from 3 months to 36 months of age, with infants from the Oslo University Hospital, Ostfold Hospital Trust, and Karolinska University Hospital [5]. Of the 1238 infants studied for allergy prevention through oral ingestion, 597 were put in the no intervention group and 641 infants were put in a food intervention group. In each group, the atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic sensitization outcomes were recorded at 12 months and 36 months. The food intervention group had a lower egg and peanut allergy diagnosis in comparison to the no-food intervention group with a 1.6% risk difference, suggesting that food allergy could be prevented in 1 out of 63 infants that participate in early allergen exposure. This finding concluded that exposure to eggs and peanuts starting from 3 months resulted in a reduction in allergy development.

Pitt et al. (2018) tracked both peanut exposure during pregnancy and via breastfeeding and direct infant ingestion, observing dietary intake of peanuts from 2 weeks to 24 months of age [6]. They specifically examined sensitization, which is a state required for an allergy to develop. 545 pregnant women from Winnipeg and Vancouver were assigned into a non-intervention and intervention group, and both groups recorded consumption of foods in dietary questionnaires completed at different intervals in the time range (2 weeks and 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 months of age). Following childbirth, mothers in the intervention group (raising 181 infants) were instructed to avoid common allergens including peanuts and eggs during breastfeeding, thus preventing indirect infant consumption via breast milk, and to only introduce solid foods after 6 months of age. The children were then tested for peanut sensitization at age 7 using a skin prick test. The study observed that children introduced to peanuts both before 12 months and from mothers in the non-intervention group were half as likely to become sensitized compared to those who did not consume peanuts before 12 months and had intervention group mothers. However, sensitization was 3.9 times more likely than the latter when mothers consumed peanuts during breastfeeding but the children did not consume them before 12 months, and 6 times more likely for children given peanuts before 12 months but the mothers did not consume them via breastfeeding. This suggests that the introduction of peanuts should be early and the form of the introduction affects the level of efficacy in preventing peanut allergies, with breastfeeding in combination with infant peanut introduction being the most effective form for early exposure.

Discussion

The case-control and randomized controlled studies that were examined carried differing themes for prebirth and postpartum outcomes in children exposed to food allergens. The overall trend for pre-birth exposure to peanuts and eggs was that the exposure decreased the likelihood of allergy development. This suggests that maternal diet and intake of food allergens can have a significant impact on fetuses after childbirth. There was no emphasis on the timing of the introduction of allergens to the maternal diet, which suggests that consistent consumption of common allergens may be contributing to the reduction of allergies. On the other hand, the postnatal studies gave differing results on the efficacy of infant allergen exposure. All but one analyzed study supported introducing peanuts and eggs to infants to reduce allergy development. The study that found no association between the early introduction of eggs and reduced development of egg allergy [7], had a different time frame. This difference in study design may have contributed to the conflicting results between the two studies. Skejerven et al. [5] started the introduction of eggs to the infant diet at 3 months while Bellach et al. [7] started from 4 to 6 months. This suggests that the time frame chosen in the second study may have been too late to be preventive for infants. More research is needed to determine if there is a point in the first year of life that is too late to begin allergen introduction in infants. This time frame may also be allergen-specific since the studies observing peanut allergy outcomes had similar results despite differing time frames, unlike for the egg allergy studies.

Pitt et al. introduced peanuts via breastfeeding as well as through direct oral intake in infants, and a combination of both routes was concluded to support the reduction of peanut allergy development. The combination of early peanut introduction in breastfeeding and oral intake held the highest yield for reduction [6]. This opens up new avenues for future research into the efficacy of allergy prevention via breastfeeding and suggests that there may need to be an overlap of preventative techniques to increase efficacy in allergy development reduction.

One common limitation among peripregnancy or prebirth studies were the mothers’ food frequency questionnaires. Recall bias was a common concern listed in the studies that used them as the questionnaires were often given after childbirth, months after the mothers began the diets they were asked to recollect. For example, the questionnaires completed by participants in the Frazier et al. study were primarily completed within a year after the pregnancy, with only 45% completed during pregnancy.

For the infant study done by Pitt et al., the sample size was quite small resulting in variable confidence intervals for the different prevention strategies. Despite the small sample size, it is an important study that observed prevention strategies during pregnancy and after birth. Further studies analyzing different prevention strategies should be completed with larger sample sizes to understand the effects of allergy sensitization with more certainty.

While discussing the limitations of individual studies examined in this literature review, it is important to address limitations within this literature review as well. One such limitation is the lack of diversity in the demographics involved in the cited studies. The sample was disproportionately focused on European populations, with only two studies venturing outside of the continent. A more expansive review should be conducted to find results more applicable to the general population as allergy trends may differ between countries.

Conclusion

This literature review examined the outcomes of introducing peanuts and eggs in both infants and fetuses to see the efficacy of allergy development reduction in both age groups. In the fetal studies, the introduction of peanuts and eggs into the maternal diet resulted in an overall reduction in allergy development and suggested a higher likelihood of allergy tolerance. In the infant studies, the findings indicated that early introduction of peanuts and eggs from 3 months and earlier reduced peanut and egg allergy development. No relationship was found between the introduction of eggs from 4 to 6-month-old infants and a reduction in allergy development. These findings indicate that both methods are effective in reducing allergies and further research should be conducted to determine if parents should use both methods as a preventative measure against allergy development. There has been conflicting research on the early introduction of food allergens but through this literature review, more clarity can be given on the efficacy of these methods. By understanding what preventative measures against allergies are effective, families can be provided more guidance in dealing with high-risk children and preventing the development of allergies.

About the Author: Rhea Zachariah

Rhea Zachariah is a class of 2024 Neurobiology, Physiology, and Behavior major and a Music minor, pursuing a future career in Medicine. Having lived with severe food allergies since birth, she wanted to explore the preventative treatments for food allergies and to try to find the most optimal time to implement these treatments. Through this paper, she hopes people will gain better insight into the current allergy treatments and so parents can make more educated decisions on food allergen introduction. Along with her interest in food allergies, she is currently researching the effects of epicatechins and valerolactones on the gene expression of lipid-stressed aortic endothelial cells in humans in a lab with Dr.Milenkovic. Outside of research, she is an active board member for the Imani student run clinic and a member of the Phi Sigma Honor Society

References

- Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. The Public Health Impact of Parent-Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2019 Mar;143(3):]. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181235. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1235

- Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, et al. Timing of Allergenic Food Introduction to the Infant Diet and Risk of Allergic or Autoimmune Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1181–1192. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12623

- Bunyavanich S, Rifas-Shiman SL, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Peanut, milk, and wheat intake during pregnancy is associated with reduced allergy and asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1373-1382. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.040

- Frazier AL, Camargo CA Jr, Malspeis S, Willett WC, Young MC. Prospective study of peripregnancy consumption of peanuts or tree nuts by mothers and the risk of peanut or tree nut allergy in their offspring. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):156-162. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4139

- Skjerven HO, Lie A, Vettukattil R, et al. Early food intervention and skin emollients to prevent food allergy in young children (PreventADALL): a factorial, multicentre, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10344):2398-2411. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00687-0

- Pitt TJ, Becker AB, Chan-Yeung M, et al. Reduced risk of peanut sensitization following exposure through breast-feeding and early peanut introduction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(2):620-625.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.024

- Bellach J, Schwarz V, Ahrens B, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of hen's egg consumption for primary prevention in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1591-1599.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.045